By Dr. Wolf Bueschgen

ANY COUNTY, USA. –The local county sheriff’s office has located a burned vehicle containing what appears to be human remains. Authorities stated the discovery was made during a joint investigation into a missing person case. The sheriff’s office noted that the Department of Natural Resources, the fire department and the county coroner’s office, including an anthropologist, assisted at the scene. Authorities have not yet positively identified the remains, but they indicated that the coroner’s office will determine the identity of the deceased.

This is often how it starts: I read about it or hear it on the news first. The details may vary — a hunter’s dog returns with a suspicious bone, a construction worker uncovers what seems like a coffin, or a boater spots something unusual floating in the water — but the task remains the same: identifying the deceased. I go about my day, and usually, the call comes in at around 3 p.m. “Hey Doc, we’ve got another one for you. Can you come by the morgue after work?” It looks like it will be another long day.

“I don’t know if you’re going to be able to do anything, Doc,” the investigator warns. “It’s all burned up. Neither the crime scene team nor the pathologist could make much headway … there’s not much left.” Over the years, I’ve learned that such statements can mean I’ll be dealing with a case of severe decomposition to complete skeletonization, and today, it was the result of a fire — truly, there wasn’t much left. A banker’s box lined with a red biohazard bag contained fourteen pounds of incinerated human remains, among other debris from a car fire. It also seems I would be at least the third person to examine these remains.

Our resident anthropologist had already begun processing what was left by the time I arrived. At the center of the stainless-steel table in the morgue was the most identifiable part: a pelvis with some lumbar vertebrae still attached. If this is all that remained, the investigator was correct — there’s not much left for positive identification, especially using dental records. Surrounding the pelvis, the anthropologist had started sorting the larger, more identifiable fragments into categories such as “long bones,” “flat bones,” and “dental.” The dental remains she had found were scant — fragments of molars, a bit of maxillary alveolar bone, and a buccal plate of the lower left mandible.

“Glove up and start sorting,” she instructed and we sifted and sorted, searching for anything that could help establish an identity or provide clues about how this person died.

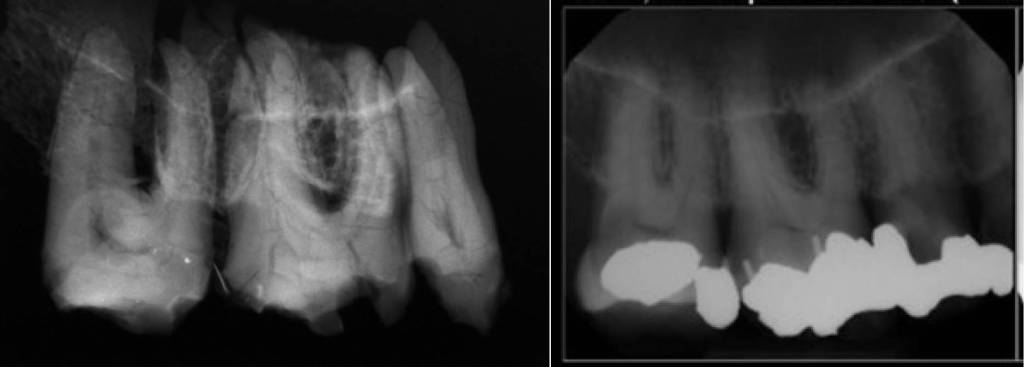

Time passed, and the fragments we were examining became smaller and less identifiable, but there were still pounds of burned, broken bone remaining. We turned to radiography for assistance with finding identifiable pieces and discovered only one more tooth. We also found screws, metal fibers and other metallic parts were mixed in with the remains, along with one rounded radiolucent object. I focused on finding this object, hypothesizing that it might be a bullet or another vital clue.

“It’s not a bullet or even metal … it’s a crown,” I said, recognizing it immediately upon sight. Blackened by the fire but otherwise intact, the crown was all that remained after the clinical crown it once covered had either burned away or -more likely- exploded when the water content in the tooth vaporized in the intense heat. The unbondable, semi-matte luster of the crown’s intaglio surface and its metallic appearance on the radiograph confirmed it was a zirconia crown, and the tooth’s morphology indicated it was a lower left molar.

The dental records I reviewed mentioned a crown on tooth #18, but no radiograph was taken after its placement. This radiograph would not have been much use anyway for comparative purposes as the tooth itself wasn’t even found. The recovered buccal plate, however, showed an unhealed alveolus for #18, indicating that this individual had this tooth at the time of death. The material listed in the records was monolithic zirconia — matching the crown I found. While this similarity alone was not sufficient for a positive ID, it was becoming increasingly convincing. At this point, nothing excluded the suspected decedent from being a match. However, no evidence was strong enough to make a definitive identification that would stand up in court. After all, how many zirconia crowns have I placed on #18? Too many to count.

When I was in dental school, we made our porcelain crowns by sculpting a powder-liquid mix onto our dies before firing them. I enjoyed the hands-on lab work, a skill and art form now largely replaced by computer-aided design. Zirconia crowns are no different; they are designed using computer programs and stored as digital files. Stone models and hand-sculpted, one-of-a-kind ceramic crowns are becoming relics of the past, giving way to infinitely reproducible crowns and digital models stored on a hard drive.

I made a call and quickly identified the lab that made the crown. After securing permission from the treating doctor and for a modest lab fee, I was able to get the crown re-made and a new model printed. I compared the re-made crown with the one from the fire and found them to be dimensionally identical. The recovered crown also fits the model in marginal, occlusal and interproximal fit, adding weight to the already convincing match.

Putting all the evidence together, I finally made a positive identification. In addition to the crown on #18, I used the two teeth found by the anthropologist (#2 and #3) and the tooth found on the radiograph of the remains (#4). These teeth fit together in a fragment of alveolar bone that also showed the maxillary sinus and remnants of amalgam and pin restorations, all matching the records of the individual believed to be the decedent.

This case exemplifies the job of a forensic dentist and showcases the capabilities of dental identification even in scenarios resulting in high destruction. Cases can be from individuals who are decomposed, skeletonized, recovered from the water, buried and even from historical contexts. Each identification results from a multi-disciplinary team comprised of coroners, sheriffs, death investigators, crime scene technicians and highly specialized team members such as pathologists, anthropologists and forensic dentists. I am excited to share some of these fascinating cases during two sessions at FDC 2025.

Wolf Bueschgen, DMD, BA, MA earned his dental degree from the Medical University of South Carolina College of Dental Medicine. He earned a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from Arizona State University and a master’s degree in biological anthropology from the University of South Carolina. He is a forensic odontologist with the Charleston County Coroner’s Office and the odontology consultant with the South Carolina Coroners and Cultural Resource Management Offices. Dr. Bueschgen maintains a private practice in Charleston, SC.

Dr. Bueschgen will present the courses “Forensic Dentistry – The Most Fascinating Sphere of Police Work” and “The Secrets Teeth Tell Us: From Archaeology to Forensic Science” on Saturday, June 21, at the Florida Dental Convention. Learn more and register at www.floridadentalconvention.com.