By: FDC2025 Speaker Pamela L. Alberto DMD

The management and treatment of impacted teeth other than third molars can be challenging. Even though the orthodontist is responsible for the overall success of the treatment plan, an interdisciplinary approach with the general dentist and the oral and maxillofacial surgeon is required. 1

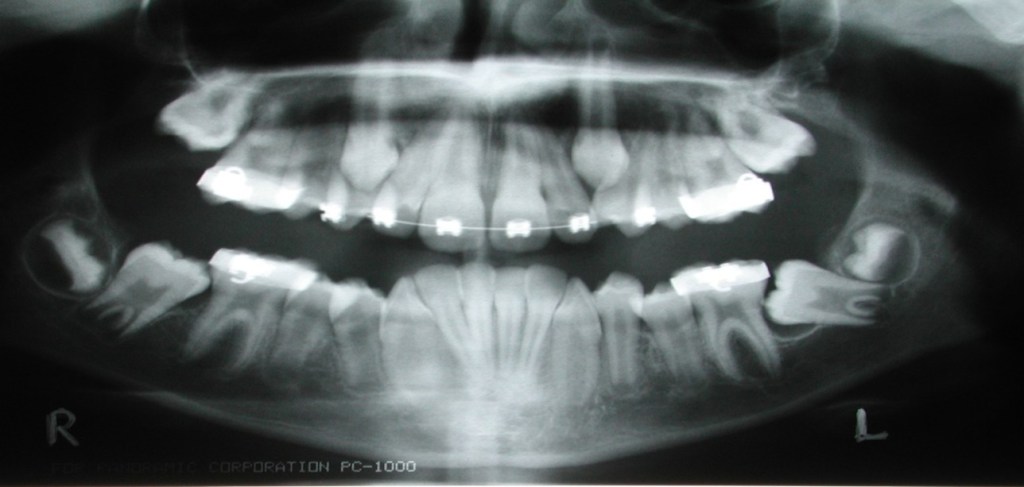

The evaluation of tooth eruption in children starts with the general dentist. Early diagnosis of any eruption disturbance will allow earlier treatment and improved success. Permanent central incisors erupt at ages seven to eight years. Lateral incisors erupt at eight to nine years. Canines erupt at ages nine to 12 years. Premolars erupt at ages 10 to 12 years. Second molars erupt at ages 12 to 13 years. (Fig.1) Identifying the lack of eruption at these time intervals is important so treatment can be initiated early. Full root formation of an impacted tooth makes it more difficult to treat.

Other than third molars, the most commonly impacted teeth are the maxillary canine, maxillary second molars, mandibular second premolars, mandibular second molars and mandibular canine. (Fig.2) The factors that contribute to the impaction of these teeth are arch length discrepancy, space deficiency, ankylosis of primary teeth, pathology and trauma.2

The overall incidents of impacted teeth are low. It is about 0.92% for maxillary canine, 0.40% for mandibular premolars, 0.13% for maxillary premolar and 0.09% for mandibular canines as reported by Dachi and Howell.3 I am finding an increase in incidence due to the lack of extractions as part of the orthodontic treatment plan.

The appropriate orthodontic treatment plan and surgical procedures will result in a predictable and stable result.

We will discuss the appropriate surgical techniques for exposing impacted canines, central incisor, canines, premolars and second molars.

Impacted Canine

Etiology

The maxillary canine starts calcification at four to five months and erupts into the oral cavity in 11 to 12 years. It remains high in the maxilla above the root of the lateral incisor and erupts along the distal aspect of the lateral incisor. The canine travels about 22mm, closing the physiologic diastema between the maxillary central incisors.

The mandibular canine starts calcification at four to five months and erupts into the oral cavity in nine to 11 years. The mandibular canine has the largest root of all the teeth. Most impacted mandibular canines are labially impacted. The etiology of impaction is most likely multifactorial. Other possible causes for impaction are trauma to the anterior maxilla or mandible at an early age, pathologic lesions, odontomas, supernumerary teeth and ankylosis.

Diagnosis and Treatment Options

Diagnosis of the canine position is a key factor in deciding treatment options. Localization of the canine requires inspection, palpation and radiographic evaluation. The lateral incisor position in the arch can also give a clue to the canine position. If the crown of the lateral incisor is proclined, the canine is lying labial to the lateral incisor. The impacted canine can occasionally be palpated on the labial or lingual aspect. Also, the resorption pattern on the root of the over retained primary canine will give you a clue as to the location of the crown of the impacted canine.

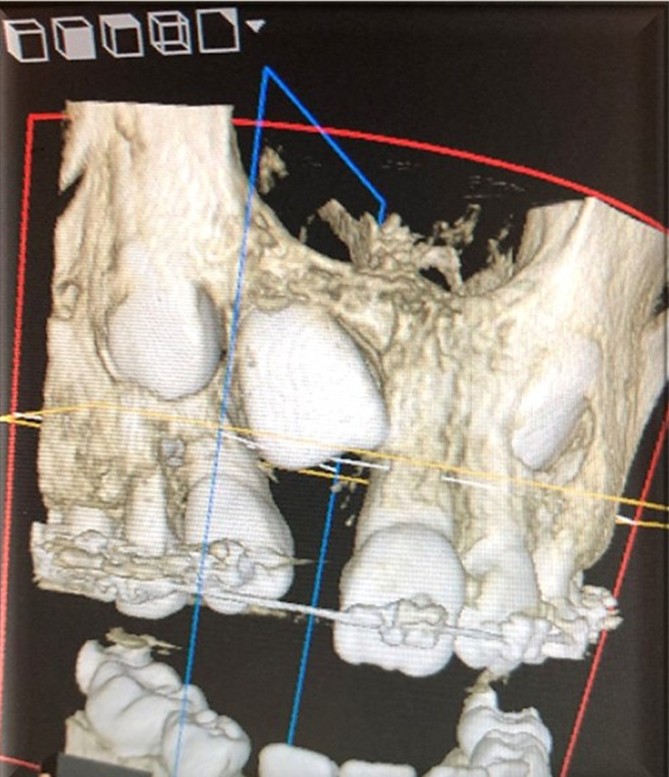

A series of radiographs can be taken to locate its position, but the 3-D Cone beam CT is superior in determining the location of the impacted canine. 4

All patients require a thorough clinical evaluation. The radiographic evaluation should include a panoramic radiograph and a 3-D CBCT to evaluate the tooth position and condition of the lateral incisor root. Then, a comprehensive treatment plan can be developed. Informed consent is a must to avoid misunderstanding, which could lead to legal problems. Management of the impacted canine can include one of the following treatment options:

- No treatment with periodic observation.

- Interceptive removal of the primary canine.5

- Surgical extraction of the canine

- Surgical exposure of the canine to aid eruption.

- Surgical exposure of the canine with eruption aided by orthodontic guidance.

- Autotransplantation of the canine

Surgical Exposure

Three methods are used for surgical exposure and orthodontic alignment .1,6

1. Open surgical exposure of the canine.

2. Surgical exposure of the canine with packing and delayed bonding of the orthodontic bracelet.

3. A surgical exposure of the canine with bonding of an orthodontic bracelet intraoperatively.

If the canine has a labial inclination, the open surgical exposure is the treatment of choice. It has been shown that excision of the gingiva over the canine with bone removal is sufficient to allow eruption of the canine 7.

A new classification for maxillary canine impactions that included guidelines for selecting the proper surgical approach was introduced by Chapokas, et al.8 The classification included three categories: Class I for palatal impactions, Class II for labial impactions or located center of the alveolar ridge and Class III for impactions located labial to the long axis of the adjacent lateral incisor root. The surgical technique was gingivectomy for Class I, closed exposure for Class II and apically positioned flap for Class III.9,10

Surgical Exposure with Orthodontic Alignment

Three surgical approaches can be used: the closed exposure technique, the window technique and the apically repositioned flap technique. The goal is to choose a technique that exposes the canine within a zone of keratinized mucosa without the involvement of the cementoenamel junction. This will minimize potential periodontal and esthetic complications following orthodontic alignment. The prognosis for alignment worsens if the inclination of the canine to the midline is greater than 45 degrees and when the impacted canine is closer to the midline. 11

Orthodontic Traction Devices

Many different devices can be applied to the crown of the tooth. A wire, pins, crown formers, orthodontic brackets and temporary anchorage devices (TADs) can be used. Wires and pins are no longer used since they can injure the crown or root of the tooth. The use of crown formers placed or cemented over the crown of the impacted tooth was popular for many years, but it also acts as a foreign body, causing inflammation and eruption. The device of choice is an orthodontic bracket or gold mesh disk with a gold chain bonded onto the canine crown surface (Fig.3). Self-cure bonding agent or a light cure bonding agent can be used. The gold mesh disk is preferred over the orthodontic brackets or buttons with the light cure bonding agent. The curing light can get at all the bonding agents through the mesh. The bonding site depends on the direction of the traction forces. The exact bonding site and direction of the gold chain exits should be decided in advance. The orthodontist should activate the appliance within a week. The orthodontist should be informed of the vector of force to be used to move the canine.

Impacted Central Incisors

The calcification of the central incisor occurs at age three to four months. It erupts at six to nine years. The treatment can be challenging due to its importance to facial aesthetics. By age eight, you need to evaluate the central incisor’s position if it has not erupted. Supernumerary teeth are the cause 47% of the time. 12, 13

Diagnosis and Radiographs

The clinical exam should evaluate the primary tooth and available space for eruption (9mm). The rotation or inclination of the ipsilateral lateral incisor is pathognomonic for an impacted central incisor. Radiographic evaluation is needed to determine its location.

The 3-D CBCT is considered the standard and has proven superior to other radiographic methods. (Fig.4)

Surgical Exposure

Surgical exposure of the central incisor can be performed in two ways. The open eruption technique and the closed eruption technique can be performed. The open eruption technique includes the window or apically repositioned flap methods. Many clinicians claim that the closed eruption technique gives aesthetic and periodontal outcomes superior to the apically positioned technique. When considering a procedure, an approach should be chosen that allows the tooth to erupt through the attached gingiva.

Impacted Premolar

Mandibular premolars have a higher rate of incidence of impaction than maxillary premolars. Calcification of the premolar occurs at 18 to 30 months. Premolars erupt at ages 10 to 13 years.

Etiology

Premolar impactions are usually due to local factors. The mesial drift of teeth due to premature loss of the primary tooth, pathology, ectopic position of the tooth bud and ankyloses of the primary tooth can cause impaction of premolars.

Diagnosis and Radiographs

A 3-D CBCT is the best radiograph to see the exact position of the impacted tooth. Understanding the tooth’s proximity to important anatomic structures (mental foramen, maxillary sinus) helps to choose the best surgical approach to exposing the impacted tooth. It is important to show the orthodontist the technical difficulty of bringing the tooth into the arch.

Surgical Exposure

The same treatment modalities are used to manage impacted premolars. Conservative management with exposure of the crown is advocated. Treating the impacted premolar is unpredictable and technically difficult. It is best to limit exposure to cases with premolars with no more than 45 degrees tilt from its normal position. 14

Impacted Second Molars

The impaction of the second molar is rare, occurring at approximately 0.03% to as high as 3%, depending on the study. It usually occurs unilaterally more commonly than bilaterally and slightly more in men than women. It is more common in the mandible than maxilla 3.

The management of impacted second molars has always been a challenge. The impacted second molar usually goes unnoticed until the orthodontic treatment is complete with full root formation.

Etiology and Radiographs

There are multiple etiologies for impacted second molars. If the developing third molar infringes on the space required for the second molar to erupt, mesial tipping will occur. Ill-fitting first molar bands can cause the mesial to impact the second molar.

Orthodontic treatment without premolar extractions has become increasingly common due to the possibility of unpleasing facial aesthetic outcomes. This has also contributed to the impaction of the second molar. A panoramic radiograph and a 3-D CBCT is recommended.

Treatment Options

The location and the degree of impaction determine the treatment plan. Observation is not an option and impacted second molars must be treated. The following treatment options can be utilized to treat the impacted second molar:

- Surgical extraction of the impacted second molar and implant placement.

- Surgically exposing and uprighting the second molar.

- Transplantation of the third molar into the impacted second molar site.

Surgically Exposing and Uprighting the Second Molar

The impacted second molar treatment plan is usually made by the orthodontist. The treatment plan may not be successful if the second molar root has more than 2/3 root formation. An orthodontic appliance needs to be placed to upright the second molar most of the time.

Temporary anchorage devices (TADs) have been developed and can be used as an anchorage device. This method is especially useful when trying to upright lingually tipped lower second molars and buccally tipped upper second molars 16.

Summary

The exposure of impacted teeth can be challenging. The decision to surgically correct these impacted teeth is usually made by the orthodontist. Treatment planning these cases should be a multidisciplinary approach. The risk-to-benefit ratio usually favors preserving the impacted tooth. In general, the recommended management of the impacted tooth is exposure with orthodontic alignment into the arch.

Pam Alberto, DMD earned her dental degree from the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine. She earned an oral and maxillofacial surgery certificate from the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey. She is a fellow of the American College of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, American Board of Forensic Dentistry, American Board of Forensic Medicine, Academy of Dentistry International, American College of Dentistry and the International College of Dentistry. She is a diplomate of the College of Dentistry in the American Association of Integrative Medicine. Dr. Alberto is the clinical associate professor in the Department of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery at Rutgers School of Dental Medicine. She is the co-founder of Cheerful Heart Missions and maintains a private practice in Sparta and Vernon, NJ.

Dr. Alberto will present the course “Surgical Exposure of Impacted Teeth” on Saturday, June 21 from 9 a.m.-12 p.m. at the Florida Dental Convention. Learn more and register at www.floridadentalconvention.com.

References

- Becker, A. and Chaushu,S. Surgical Treatment of Impacted Canines: What the Orthodontist Would Like You to Know. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin N Am 27 (2015) 449-458

- Thilander, B. and Jacobasson. S.O. Local Factors in Impaction of Maxillary Canines. Acta Odontologies Scandinavica. 1968; 26: 145-168.

- Dachi SF, Howell FV. A Survey of 3874 routine full mouth radiographs. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology 1961; 14:1165-309

- Altan A, Colak S, et al. Radiographic Features and Treatment Strategies of Impacted Maxillary Canines. Cumhuriyet Dental Journal:2019;23(1)

- Jacobs S.G. Reducing the Incidence of Unerupted Palatally Displaced Canines by Extraction of Deciduous Canine. The History and Application of this Procedure with some case reports. Aust Dent J. 1998;43 (1): 20-7.

- Jacobs S.G. Reducing the Incidence of Unerupted Palatally Displaced Canines by Extraction of Deciduous Canine. The History and Application of this Procedure with some case reports. Aust Dent J. 1998;43 (1): 20-7.

- Piriren, S., Arte, S. & Apajalahti, S. Palatal Displacement of Canine is Genetic and Related to Congential Absence of Teeth. 1998; Journal of Dental Research 75:1742-1746.

- Chapokas, A.R. Almas,K. and Schincaglia, G-P. The Impacted Maxillary Canine: a Proposed Classification for Surgical Exposure. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012; 113:222-228.

- Bedoya,M. and Park,JH. A Review of the Diagnosis and Management of Impacted Maxillary Canines. JADA. Dec.2009, Vol.140.

- Koutzoglou, S.I. and Kostaki. Effect of Surgical Exposure Technique, Age, and Grade of Impaction on Ankylosis of an Impacted Canine, and the Effect of Rapid Palatal Expansion on Eruption: A Prospective Clinical Study. American Journal of Orthodontics & Dentofacial Orthopedics 2013; 143:342-52.

- Felsenfeld A, Aghaloo T. Surgical exposure of Impacted Teeth. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin N Am. 2002;14: 187-199.

- Smailiene D, Sidlauskas A, Bucinskiene J. Impaction of the Central Maxillary Incisorassociated with Supernumerary Teeth: initial position and spontaneous eruption timing. Stomatologija 2006;8(4): 103-7.

- Borbely, P. Watted, N. Dubovaka, I. Hegedus, V. and Muhamad, A-H. Orthodontic Treatment of an Impacted Maxillary Central Incisor Combined with Surgical Exposure. Inter J of Dental & Health Sciences 2015;2(5):1335-1344.

- Majunatha,B.S. Chikkaramaiah,S. Panja, P. Koratagere, N. Impacted Maxillary Second Premolars: a Report of Four Cases. BMJ Case Rep 2014. Doi:10.1136

- Desnoes H. Abnormalities in the development of the second molars and orthodontic treatment without extraction of premolars. Management of posterior crowding. J Dentofacial Anom Orthod 2014;17:406

- Going Jr. R., Rayes-Lois, D. Surgical Exposure and Bracketing Techniques for Uprighting Impacted Mandibular Second Molars” JOMS. 1999; 57: 209-211.