By Dr. Jaqueline Plemons, Florida Dental Convention 2023 Speaker

Introduction

The mucosal surfaces of the oral cavity provide a canvas for a variety of common and some not-so-common oral lesions and conditions. Mucosal diseases vary greatly in appearance and can present as red, white and/or ulcerative areas affecting a single or multiple sites. They may be asymptomatic or cause discomfort that negatively affects quality of life.

Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions appears to vary with age affecting approximately 5% of people in their 20’s and increasing to nearly 20% of individuals aged 70-80 years.1 Numbers can be significantly higher in certain populations.

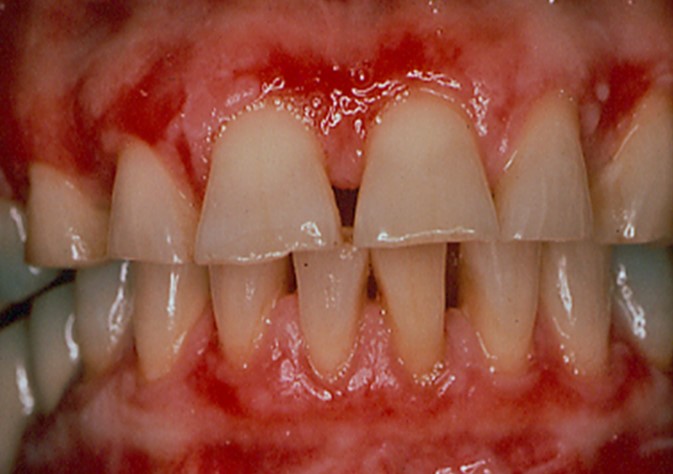

Figure 1 & 2: Lichen planus occurring on the gingiva (desquamative gingivitis) and tongue (plaque-like form).

The etiology of oral mucosal diseases and conditions includes infection, trauma, altered immune-response and neoplastic changes. A detailed patient history is often critical to establishing a definitive diagnosis. Patients most commonly seek care for oral mucosal pain from their general dentist.

This paper explores mucosal changes seen with dermatologic diseases such as lichen planus, mucous membrane pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris; recurrent aphthous and herpetic stomatitis; and oral contact or allergic reactions.

Dermatologic Conditions:

Lichen Planus

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory disease resulting from an abnormal T-cell mediated immune response to a yet unknown lichen planus specific antigen. It can cause skin and/or mucosal lesions, affecting slightly more females than males. Symptoms vary from mucosal sensitivity to continuous debilitating pain, however, some patients are asymptomatic and unaware of their lesions prior to clinical examination.

Lichen planus affects 0.5-2% of the general population.2 The buccal mucosa is the most affected site followed by the tongue and gingiva. Lesions may persist for years with periods of exacerbation and quiescence. Lichen planus is occasionally associated with diabetes and hypertension, and more recently with hepatitis C infection. Lichenoid changes are also seen with drug reactions, contact reactions and chronic graft-vs-host disease.

Lichen planus presents in various forms in the mouth including reticular, plaque-like, papular, atrophic, ulcerative, and bullous forms. Lesions range from asymptomatic, white lacy lines (Wickham’s Striae) in the reticular form and dense thickening of the mucosa in the plaque-like form to erythema and ulceration in the atrophic and ulcerative forms. In the former, patients may complain of sensitivity to spicy, acidic and rough-textured foods as well as difficulty with oral hygiene. (Figures 1-2)

A diagnosis based on clinical examination is often acceptable in patients with reticular lichen planus, however, histologic evaluation may be necessary to arrive at definitive diagnoses for the other forms. Direct immunofluorescence may be useful when distinguishing between lichen planus and other oral desquamative diseases.

The cornerstone of treatment of oral dermatologic diseases including lichen planus is the use of high potency topical steroids such as clobetasol and fluocinonide. With severe episodes, tapering doses of systemic steroids are often prescribed as well. Topical steroid therapy can be enhanced by using steroid delivery trays, and intralesional steroid injections may be considered for ulcerative lesions on movable mucosa. Other immune suppressants, both topical and systemic, are used in refractory cases where collaboration with a physician is warranted. Patients often benefit from avoiding products that may irritate the oral tissues including strong flavored toothpaste and mouth rinses as well as spicy, acidic, or rough-textured foods.

Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid

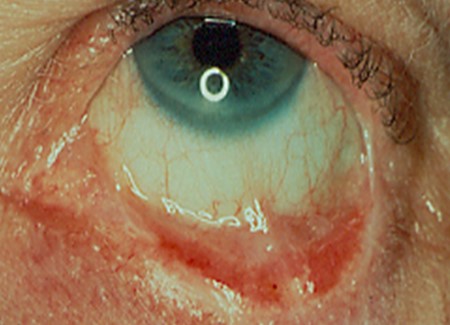

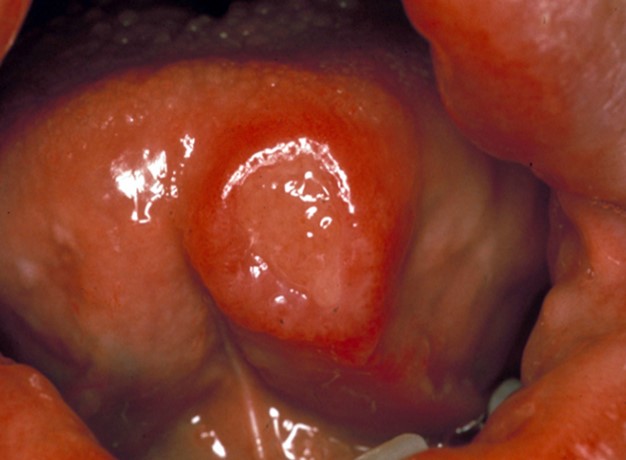

Figure 3-5: Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) presenting as desquamative gingivitis; poor plaque control resulting from the inability to brush comfortably; patient responded well to topical steroids applied in delivery trays.

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) is an autoimmune blistering disorder that affects the oral &/or other mucosal surfaces. It affects women twice as often as men and occurs most frequently in the 5th to 7th decades of life.2 Clinically, MMP presents as desquamative gingivitis (bright red gingiva) often showing a positive Nikolsky’s sign (sloughing of the outer surface of the oral mucosa with slight rubbing). (Figures 3-5)

Vesiculobullous lesions occasionally occur on other mucosal surfaces such as the conjunctiva, genitals, skin, nares, esophagus, urethra, and rectum. Symblepharon formation (scarring extending from the conjunctiva to the eyeball itself) can lead to blindness. (Figure 6) It is wise to refer patients for an evaluation by an ophthalmologist following diagnosis. Biopsy for routine histology and direct immunofluorescence is often necessary for a definitive diagnosis. Specimens will show a clean, sub-basilar separation of the epithelium from the underlying connective tissue.

Treatment of MMP usually begins with medications and techniques previously described for oral lichen planus – topical and/or systemic steroids applied via various techniques. Systemic therapy with doxycycline or dapsone has shown value in the management of patients with MMP along with other medications which are prescribed by physicians due to their complex side-effects and monitoring demands. More recently, biologics have been used in patients who have not responded to more conventional therapy or have high risk side effects.

Pemphigus Vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is another autoimmune blistering disorder affecting the skin and/or oral mucosa. Autoantibodies against proteins in the skin called desmogleins are produced causing a suprabasilar separation of epithelial cells from one another. Approximately 50-70% of patients with pemphigus vulgaris develop mucosal lesions.3 Middle-aged and older adults are most often affected, males and females equally. A mortality rate of approximately 5-15% has been reported.

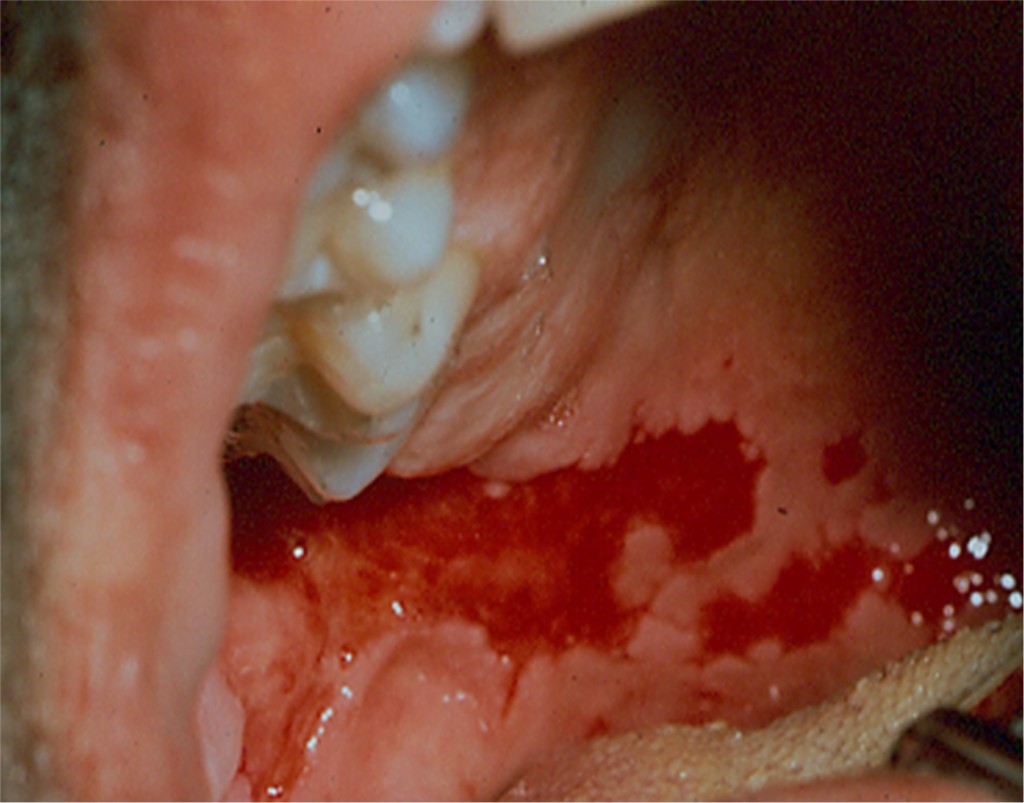

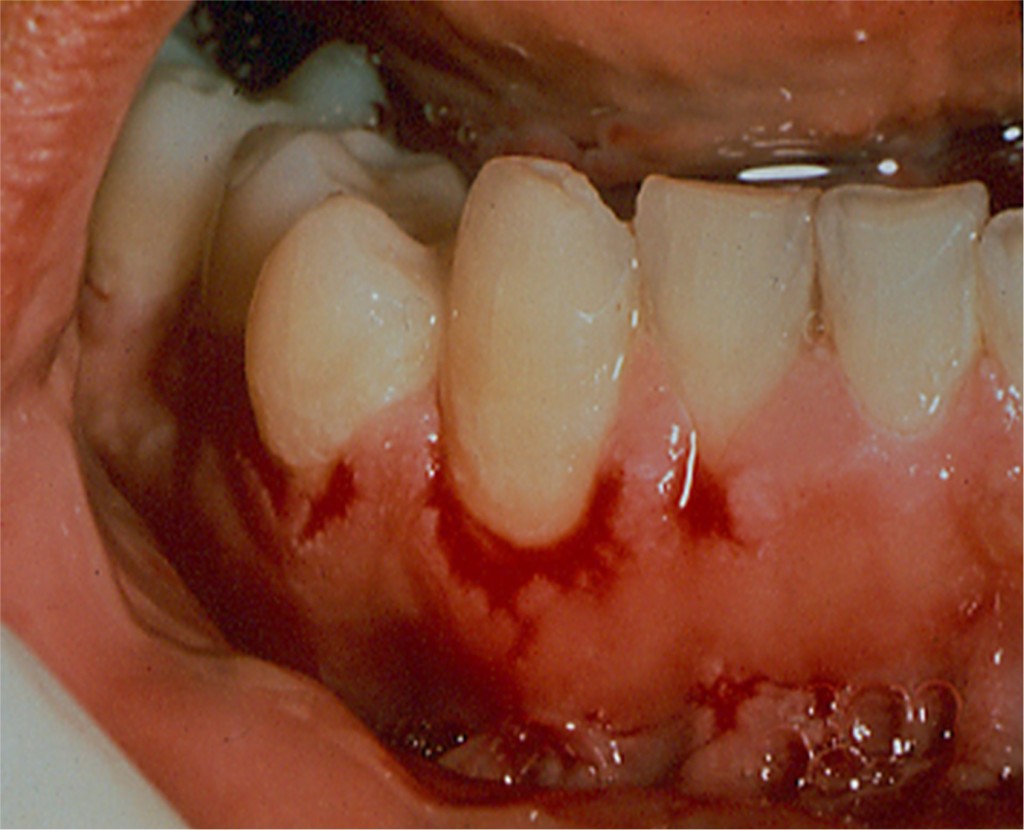

Oral manifestations of pemphigus vulgaris include bullous lesions, erosions with ragged borders, desquamative gingivitis and a positive Nikolsky’s sign. (Figures 7-8) Multiple large lesions on the skin can result in fluid loss, electrolyte imbalance, septicemia and death.

Diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris is determined by routine histology and direct immunofluorescence following biopsy. Treatment of minor lesions confined to the oral mucosa may initially be managed with topical and/or systemic steroids, however, patients often require other systemic immunosuppressants or biologics. A team approach to treatment including both dentists and physicians is required.

Recurrent Oral Ulcerations

Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis

Aphthous ulcers (canker sores) are common oral lesions affecting mucosal surfaces (labial/buccal mucosa, tongue, soft palate and floor of the mouth) in approximately 20-30% of the population. Most patients experience lesions prior to the age of 30 (80%), and the problem often runs in families.4 Patients may experience only an occasional aphthous ulcer; however, some suffer from multiple painful recurrent lesions that negatively affect quality of life. It is these patients who seek care from their dentist.

Figure 7 & 8: Erosions with ragged borders seen with pemphigus vulgaris.

Minor aphthae occur as single, or multiple painful circular/ovoid ulcers with fibrinous coatings surrounded by erythematous borders. They range from 2-3 mm in diameter (<1cm) and typically persist for 7-10 days. Major aphthae are larger, deeper, and often last for weeks. (Figures 9-10) Patients may experience systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise, and lesions are said to heal with scarring. Herpetiform aphthae are far less common and present as multiple very small ulcerations (clinically similar to herpesvirus lesions) which may coalesce forming larger areas of ulceration.

Factors associated with recurrent aphthous stomatitis include tissue trauma, psychological stress, gastrointestinal disease, blood dyscrasias, vitamin deficiencies, immunosuppression, food reactions, medications (NSIAD’s) and oral hygiene products (sodium lauryl sulfate). A thorough medical and dental history is paramount to the successful management of patients with chronic oral ulcerations.

Treatment of aphthous stomatitis often begins with the use of topical agents such as chlorhexidine or steroids including triamcinolone, fluocinonide or clobetasol. Systemic steroids are considered in severe cases along with other immune modulating drugs prescribed and monitored by physicians. Intralesional steroid injections are useful for isolated refractory lesions. Vitamin supplementation and diet manipulation may be useful along with discontinuation of targeted medications. Several over-the-counter products are marketed for treatment of aphthous ulcers, and patients may benefit from laser therapy.

Recurrent Herpetic Stomatitis

Recurrent herpetic stomatitis represents the attenuated form of the primary infection with Herpes Simplex 1 virus, usually occurring in childhood. After initial exposure, the virus remains latent in the trigeminal ganglion and uses the axons of sensory neurons to move back and forth to the skin or mucosa. Recurrent (secondary) herpes infection occurs with reactivation of the virus.5

In contrast to recurrent aphthous stomatitis, recurrent herpetic lesions occur unilaterally on non-movable keratinized tissue that is attached to the underlying bone (hard palate and attached gingiva). Ulcerations are preceded by multiple small vesicles which quickly rupture forming ulcers that coalesce creating larger ones. (Figure 11) Lesions are usually painful and last around two weeks during which time transmission may be possible. Patients often experience a prodrome or warning of an impending lesion characterized by tingling, itching, or burning. Herpes labialis occurs in the same manner but is not included in recurrent herpetic stomatitis because it affects the outer portion of the lips.

Figure 9 & 10: Minor aphthous ulcer presenting as a small painful lesion with a fibrinous coating and erythematous border inside the lower lip. Second picture shows a large painful ulcer consistent with major aphthous stomatitis which has been present for several weeks.

Reactivation of the virus is associated with stress, fatigue, fever, upper respiratory tract infections, trauma, sunlight, hormonal changes and foods. It is more commonly seen in immunocompromised patients. Information regarding reactivation or triggering of the virus should be explored during patients’ health history.

Treatment of recurrent herpetic stomatitis includes prevention as well as topical and systemic medications. Lesions may be preempted by avoiding sunlight or using a protective sun blocking agent, avoiding triggering foods or drinks, and taking lysine. Once a lesion has occurred, there are several over-the-counter products such as 10% docosanol that provide symptomatic relief as do prescription topical medications including 1% penciclovir and 5% acyclovir. Systemic therapy with acyclovir and valacyclovir is the cornerstone of antiviral treatment.

Contact Reactions

Oral Contact Stomatitis

Oral contact stomatitis is an inflammatory condition caused by exposure of the mucosa to a variety of substances resulting in pain, burning, swelling, erythema (oral and perioral), peeling, and blisters/ulcerations. (Figures 12-13) Reactions often begin within minutes to hours. The most common sites affected include the buccal/labial mucosa, lateral borders of the tongue, gingiva, and hard palate. Clinical changes can be localized, follow the shape of oral appliances, or can be more generalized such as that seen with exposure to mouth rinses or toothpastes.

Signs and symptoms of acute contact stomatitis usually develop shortly after exposure to irritants while the chronic form occurs in areas of long-term exposure to materials such as dental restorations and appliances.6

Contact stomatitis in the mouth occurs less frequently than contact dermatitis on the skin due to saliva, which constantly dilutes offending agents, and the relatively short time substances have in contact with mucosal surfaces as a result of the high degree of vascularization in the mouth.

Summary

Common causative agents associated with oral contact stomatitis include oral hygiene products; candy, gum, or mints; sodas; flavorings agents (cinnamon) and preservatives (benzoic acid); foods such as processed tomato products; and dental materials.

Diagnosis of oral contact stomatitis is based primarily on history of present illness and clinical examination. Treatment begins with changes in oral hygiene products and an elimination diet which should result in improvement or resolution within two to four weeks. Topical steroid therapy may be useful for more severe cases, and biopsy confirmation may be indicated to rule out systemic disease. Patch testing can be of benefit in identifying causative agents, and replacement of dental restorations may be considered if lesions are consistent in location.

Clinical evidence suggests that oral mucosal lesions and conditions may be more prevalent now than in the past. Diagnosis can be difficult as signs and symptoms of oral mucosal lesions are often similar, making diagnosis a challenge. Patients often seek care from multiple dental and medical providers before receiving a diagnosis and effective treatment. Knowledge of oral mucosal diseases will not only help patients but will also give dentists the tools to provide optimal care.

Figure 12 & 13: Generalized diffuse erythema consistent with oral contact stomatitis associated with use of cinnamon-flavored chewing gum (before and after discontinuing product).

REFERENCES

- Splieth CH, Sümnig W, Bessel F, John U, Kocher T. Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in a representative population. Quintessence Int. 2007 Jan;38(1):23-9. PMID: 17216904.

- Schlosser BJ. Lichen planus and lichenoid reactions of the oral mucosa. Dermatol Ther. 2010 May-Jun;23(3):251-67. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01322.x. PMID: 20597944.

- Schmidt E, Groves R. Immunobullous Diseases. In: Griffiths C, Barker J, Bleiker T, Chalmers R, Creamer D, editors. Rook’s textbook of dermatology. 9th Ed. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell 2016; 50.1-.57.

- Barrons RW. Treatment strategies for recurrent oral aphthous ulcers. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(1):41–50.

- Arduino, Paolo Giacomo, and S. R. Porter. “Oral and perioral herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV‐1) infection: review of its management.” Oral diseases 12.3 (2006): 254-270.

- LeSueur, Benjamin W., and James A. Yiannias. “Contact stomatitis.” Dermatologic clinics 21.1 (2003): 105-114.